I’m going to be terribly gauche and start by quoting myself (kids, don’t try this at home). Last year, in my review of The Wolf Man (1941), I wrote:

In the early to mid 20th century, Universal Pictures produced an iconic run of horror movies, starting with 1931’s Dracula and ending in 1956 with The Creature Walks Among Us. These films largely defined the images of classic monsters in the American public consciousness.

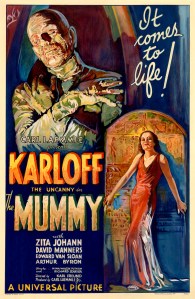

This Octoberween, I’m going back to Universal’s third classic horror film in a row. The Mummy wasn’t the first movie to use a mummy as a monster, and it certainly didn’t start the West’s obsession with ancient Egypt (there’s a long and storied history there, perhaps better covered in a mildly informative TikTok or even a book of some sort). All the same, it set the standard for Hollywood and beyond. Once again, Jack Pierce’s outstanding makeup design seared an image into audiences’ collective imagination for generations to come. From Scooby-Doo to Brendan Fraser, this is the foundational text of the mummy in American media.

The Mummy (1932):

The Plot: Ten years after his father’s (Arthur Byron) ill-fated discovery of the mummy Imhotep’s (Boris Karloff) tomb and the cursed Scroll of Thoth, archaeologist Frank Whemple (David Manners) discovers the tomb of the mummy’s lover Anck-es-en-Amon. Now appearing as the human Ardath Bey, Imhotep stalks the houses and museums of Cairo, searching for the reincarnated soul of his lost love. He may have found it in half-Egyptian socialite Helen Grosvenor (Zita Johann). Will Helen be able to avoid becoming the vessel for a long dead princess? Will Frank and family friend Dr. Muller (Edward Van Sloan) escape the mummy’s curse? Will Anck-es-en-Amon be happy to see Imhotep? Sometimes, Mummy doesn’t know best (sorry, sorry, I’ll show myself out).

Following the twin successes of 1931’s Dracula and Frankenstein adaptations, Universal Pictures wanted to keep the hits coming with another horror film featuring their new star “Karloff the Uncanny” (1). This being pre-internet, Egyptomania sparked by the opening of Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1923 was still going strong a decade later instead of fading from the public consciousness within a few weeks*. The West’s fascination with all things ancient Egypt certainly pre-dates the Carter expedition (hello, Napoleon!), but the Egyptian Revival in art and architecture was still going strong in the early 1930s.

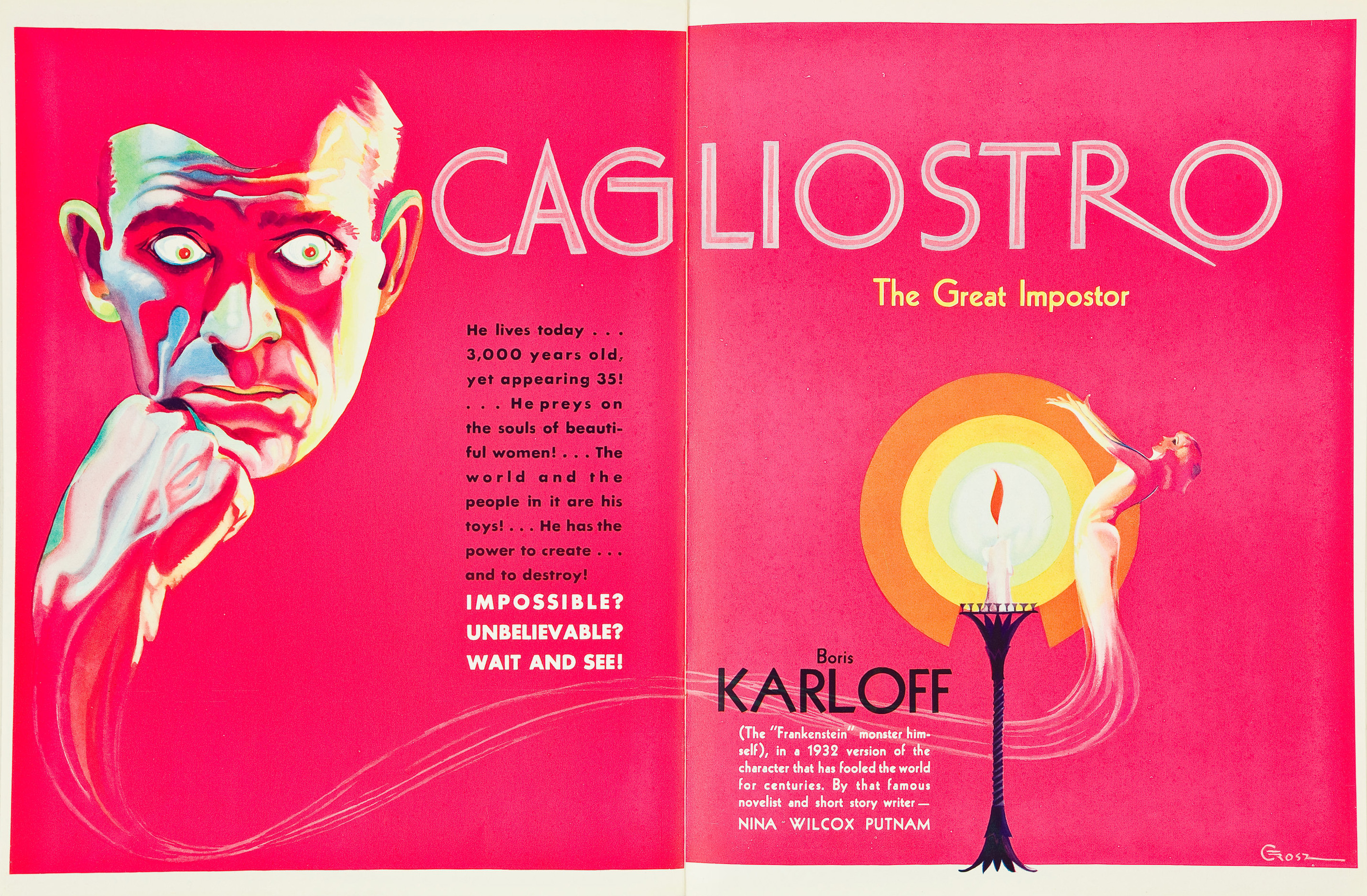

Studio head Carl Laemmle Jr. tasked writers Richard Shayer and Nina Wilcox Putnam (who also wrote the first draft of the 1040 tax return, and you can bet I’ll be remembering that in April) with writing a treatment drawing on the fabled King Tut’s Curse for inspiration. Shayer and Putnam came back with Cagliostro, a San Francisco-set tale of an immortal Egyptian magician hunting women who look like the lover who dumped him centuries earlier (2)**.

Universal hired John L. Balderston, whose stage adaptation of Dracula had recently been used as the basis for the Bela Lugosi film, to pen the script. His previous life as a journalist made him especially suited for the job: While writing for the New York World in 1923, he was one of the reporters present for the opening of King Tut’s tomb (1).

Balderston changed the film’s setting to Cairo, named the mummy and his lost love after actual ancient Egyptians (an architect of the Third Dynasty and Tutankhamun’s wife, respectively), and altered Imhotep’s motivation from general woman-hating to a singled-minded attempt to resurrect his dead lover whatever the cost (2). He also seems to have recycled some characters and scenes from Dracula. Frank and Dr. Muller have more in common with Johnathan Harker and Dr. Van Helsing than just being played by the same actors. Dr. Muller even has a similar “cards on the table, I know you’re a monster” confrontation with Imhotep. Hey, if it ain’t broke…

It’s impossible to say whether Cagliostro would have had the same impact as The Mummy–I’m not an immortal Italian wizard, after all–but it’s hard not to think that Balderston made the right calls here. The Cairo setting is certainly more exotic than San Francisco. More importantly, the contrast between modern Cairo and ancient Egypt adds an extra layer to Imhotep’s tragedy: “Anck-es-en-Amon, my love has lasted longer than the temples of our gods.” It’s a hell of a thing to wake up after thousands of years to find your entire way of life replaced by hot jazz and British archaeologists.

While undoubtedly a classic, The Mummy is not without its flaws. In addition to the aforementioned plot and character similarities to Dracula, there is surprisingly little mummy action. It’s a testament to Jack Pierce’s makeup design that Karloff’s appearance seeped into the public consciousness as it did, since the Mummy is only onscreen as a mummy for maybe 2 minutes in the prologue of the film. Director Karl Freund uses the bandaged mummy sparingly but effectively. We see the Mummy open his eyes and then slowly lower his arms, tearing through dusty wrappings. After that, we only see a decayed hand reach for the Scroll of Thoth, and then trailing bandages moving towards the door. Bramwell Fletcher’s look of terror and hysterical laughter are more frightening than any mummy. Still, I feel a little bad for Boris Karloff, who spent eight hours in the makeup chair for that fleeting appearance (1).

The greatest strength of The Mummy is that Imhotep is a sympathetic–even tragic–figure. Boris Karloff plays the role with a quiet dignity. Even as he threatens the protagonists and commits to his ultimately self-desctructive path, there is a genuine warmth to his interactions with Helen. Like James Whale before him, Freund makes good use of Karloff’s captivating eyes, which can show sadness and menace in equal measure.

Imhotep is a necromancer and murderer, perverting the laws of nature and ultimately incurring the wrath of the gods. The tragedy lies in his motivation: Not a lust for power, or even fear of his own death. He is a grieving lover, willing to break the most sacred rules of his faith to resurrect Anck-es-en-Amon. Anyone who’s been in love will at least understand the impulse***.

Alas, in his grief, Imhotep becomes monstrous. He succeeds in transferring Anck-es-en-Amon’s spirit to the innocent Helen Grosvenor’s body, but their reunion is soon marred by her horror at her beloved’s decaying form and blasphemous actions. Anck-es-en-Amon “awakens” in the Cairo Museum, not even aware that she died in the first place: “Where are we? This is my bed, but this is not the temple nor my father’s palace.” Though initially confused, she is also grateful, thinking that the gods have finally forgiven them for their forbidden romance. Her relief turns to fear and disgust when Imhotep reveals his plan to kill, mummify, and reanimate her so they can be together as human mummies. Not only have the gods not forgiven them, but every action Imhotep has taken since her death has led him down a dark and sacrilegious path. Anck-es-en-Amon tells Imhotep what he should have realized 3,700 years ago: “I loved you once, but now you belong with the dead.”

When Frank and Dr. Van Helsing Muller arrive and distract Imhotep, Anck-es-en-Amon prays to a statue of the goddess Isis, begging to be saved. Isis destroys the Scroll of Thoth and reduces Imhotep to a pile of dust and bone. The modern heroes are saved by divine intervention, but only at the behest of the Mummy’s lost love.

The true danger presented by The Mummy, and by many tales of necromancy or science run amok, is the failure to accept death as a natural part of life. A difficult task to accomplish in the throes of loss, but one that allows the living to heal and still honor the dead. As we cede increasing amounts of personal data to money-grubbing corporations that have already started making ethically dubious, AI-fueled digital recreations of dead actors, maybe it’s healthy to revisit these stories. After all, death is part of what makes us human. Forgetting that can make us monstrous.

*That’s not entirely fair. It took around 10 years to excavate and catalogue the contents of the tomb, so it’s not like the public got one news story and that was that.

**They may have borrowed the name from notorious (and Italian) 18th century occultist Giuseppe Balsamo, a.k.a. Count Alessandro di Cagliostro, although a quick perusal of his Wikipedia page suggests that he did not achieve immortality. Again, this was pre-internet. (2)

***As modern audiences who have seen The Simpsons, we of course know better than to raise the dead.

- Mallory, Michael. Universal Studios Monsters: A Legacy of Horror. Universe Publishing, 2021.

- Cowrie, Susan D., and Tom Johnson. The Mummy in Fact, Fiction and Film. McFarland and Company, Inc., Publishers, 2002.

Pingback: Octoberween: ‘The Lure’ is a Grimy, Lovely Fairy Tale | Rooster Illusion