Another Octoberween draws to a close. Ah, the passage of time. Makes ya think. As always, we had a blast getting in that holiday spirit. Second Breakfast re-visited Van Helsing, a bangin’ good time if there ever was one, and also the movie that taught me Frankenstein’s Monster could speak. Go figure. Sarah returned with a /horror review of Dark Harvest, the latest painterly chiller from 30 Days of Night director David Slade (at the risk of overusing a phrase, that one also sounds like a bangin’ good time). Yours truly went back to the classics with The Wolf Man. Like I said, we had a blast.

Our twelve dedicated readers will surely remember that last year I wrapped things up with a review of Francis Ford Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula, a flawed movie for which I developed a grudging appreciation.

I’d long been aware of Kenneth Branagh’s similarly titled Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, and thought it might be a fun follow-up to the Dracula film that had come out just two years earlier. Evidently, so did Francis Ford Coppola. While doing some supplementary research for this review–don’t be too impressed, I just wanted to see if Kenneth Branagh had ever written down what the hell he was thinking–I learned that the film was produced by Coppola’s American Zoetrope in conjunction with TriStar Pictures, with Coppola even providing “on-set consultation during rehearsals and early phases of photography”.(1)

That’s more of an interesting factoid than a launching point for insightful criticism, which is why it’s in the introduction and not the body of the review. Still, it’s a decent indication of the kind of movie Branagh and co. set out to make: An ostensibly “faithful” adaptation with contemporary sensibilities, aimed at an adult audience. To quote the director himself:

“Since this film is Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, our intent was always to arrive at an interpretation that’s more faithful than earlier versions to the spirit of her book.” (1)

Let’s see how that worked out.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1994):

The Plot: After his mother dies giving birth to his younger brother, brilliant college student Victor Frankenstein (Kenneth Branagh) dedicates himself to finding a way to end all death. The young scientist does succeed in imbuing life into a patchwork man assembled from pilfered corpses, but immediately abandons his creation in horror. The Creature (Robert DeNiro) learns to speak by observing a peasant family unseen, but every attempt to enter society is met with violent fear. Knowing only pain and rejection, the Creature vows revenge upon his Creator. Will anyone in Victor’s family survive? Will the Creature ever find peace? Will Victor ever take responsibility for his actions? Wow, “no’s” across the board. Oof. Yowza.

The earliest adaptation of Frankenstein that I could find, after an admittedly cursory search, was Richard Brinsley Peake’s stage production in 1823, titled Presumption; or, the Fate of Frankenstein (2). In the intervening years between then and 1994, there were, shall we say, quite a few other adaptations for stage and screen. For brevity’s sake, I’m willing to bet that Branagh was referring to the 1931 film Frankenstein, directed by James Whale, when he mentioned less faithful “early versions” of the story. It’s a reasonable assumption, since, like The Wolf Man a decade later, Universal’s Frankenstein came to define the monster in the public imagination (thanks again in part to Jack Pierce’s brilliant makeup work). To this day, the name “Frankenstein” conjures images of Boris Karloff with bolts sticking out of his neck.

This is a review of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, not Frankenstein, so I won’t spend too much time on the earlier film, but I did want to say a brief word in its defense: Despite making drastic changes to the plot, Frankenstein retains the spirit of the novel and characters. The Creature may not speak, since the action has been condensed to days rather than years, but he remains a sympathetic character, the victim of his creator’s neglect and mankind’s hostility. Karloff gives a moving and subtle physical performance that often gets mis-characterized thanks to what I’ll call the Munster-ification of the creature design in the ensuing decades. The changes to the novel even make Frankenstein (here Henry, for some reason) a more sympathetic character, one who recognizes that he is to blame for the Creature’s actions and attempts to take responsibility. While it’s certainly not a literal translation of the novel, I’d argue that it’s a perfect adaptation. It functions on its own terms as a film without losing the book’s core tragedy. In a way, Frankenstein is no less faithful for all its surface-level changes.

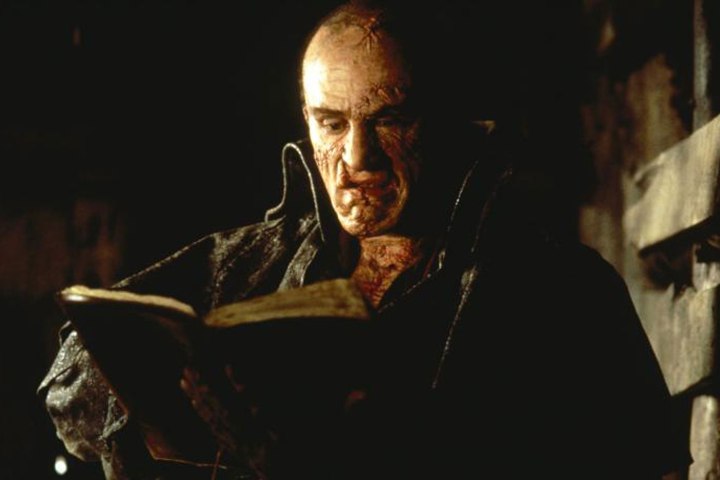

To be fair to Branagh, he does hew much more closely to the novel’s story, even including the framing device of a dying Victor telling his tale of woe to an ice-bound Arctic explorer. He also keeps Victor’s love interest Elizabeth’s role as his adoptive sister, which plays a little differently now than it would have in 1818, but I’m not really getting into all that. The most significant inclusion, probably more important even than setting the film in eighteenth-century Geneva, is the Creature’s intellectual growth. The Creature of Branagh’s film–and Shelley’s novel–is well-spoken and capable of asking difficult questions. Questions like “why was I created?” and “do I have a soul?” Yes, he becomes monstrous through his campaign of revenge against Frankenstein, but how much can one really blame him? Like the rest of us, he didn’t ask to be made, but unlike most viewers he never experiences love or kindness first-hand. De Niro plays the character well, finding the aching need beneath the rage and makeup. He especially shines in the film’s quiet moments. Unfortunately, those are few and far between.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein has two cardinal sins, as far as I’m concerned. First, it takes an already melodramatic story and dials every emotion up to eleven. It’s the type of film where multiple characters shout “NOOOOOOOOO!!!!” after some new tragedy. At times the energy almost reminds me of the “Where’s the phone?!” scene in Wet Hot American Summer, which probably is not the direction the filmmakers are going for in this very serious literary adaptation for grown ups. I’ve come to appreciate Kenneth Branagh as a filmmaker, but he does have a weird tendency to pick one stylistic flourish and then use it way too many times in a film. In Thor, it was Dutch angles. Here, it’s whirling the camera around the actors in moments of heightened feeling, of which there are quite a few. It’s not an ineffective technique, but it is distracting when repeated to this extent.

Much more disastrous is the choice to treat Victor Frankenstein as a sympathetic character without really changing his behavior. Here–and, it’s true, in the novel as well–Victor is an arrogant, selfish coward who for some reason the audience is meant to view as a tragic romantic hero. His great flaw is not his ambition or even his lax attitude towards grave robbing, but rather his utter refusal to accept any responsibility for his creation. The Creature’s murderous rampage is the consequence of Victor’s neglect, not some run of ill fortune befalling him for no reason. Branagh plays the character with such exuberance–and smoldering intensity, in some scenes–that it’s clear he sees him as an essentially decent man who gets carried away by his own noble intentions. In the director’s own words:

“This is a sane, cultured, civilized man, one whose ambition, as he sees it, is to be a benefactor of mankind. Predominantly we wanted to depict a man who was trying to do the right thing.” (1)

Again, this is how Victor is characterized in the novel as well, so it is more “faithful” than the 1931 film’s somewhat maniacal interpretation. Still, I can’t help but feel that Branagh the director is too enamored with Branagh the actor to really give the character his due as a sniveling coward. This is, after all, the same man who in the book allows his friend Justine to be hanged after the Creature frames her for murdering his young brother. Victor stands by while thinking about how much worse he has it than the woman about to be wrongfully executed for killing a child:

“The tortures of the accused did not equal mine; she was sustained by innocence, but the fangs of remorse tore my bosom, and would not forego their hold.” (3)

Branagh at least changes the book’s lengthy trial to a lynch mob, so that Victor can arrive just too late to save her, but all attempts to turn the character into a man of action fail to account for his moral cowardice. His great sin is not playing God and creating life–although, as we all learned from Jurassic Park, it’s probably not a good idea to play God–but abandoning his creation and never owning up to his own mistakes, no matter how many people die.

Perhaps I’m being unfair. It’s not that I think all protagonists must be paragons of virtue, or that a filmmaker needs to turn to the audience and say “by the way, this is bad behavior.” I just really have it out for this character. Victor Frankenstein is a weenie, and that’s apparently a hill I’m willing to die on. So much for impartial film criticism.

Other than its attempted rehabilitation of one of classic literature’s greatest poltroons, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein does make some interesting choices. In the novel, the Creature asks Frankenstein to make him a female companion. After much hemming and hawing, Victor eventually refuses, and the matter is never really brought up again except when the Creature is listing grievances. In the film, a grief-stricken Victor attempts to bring Elizabeth (Helena Bonham Carter) back from the dead after the Creature murders her. He stitches her corpse together with Justine’s remains and succeeds in animating the thing, but what little of his sister/wife (still not getting into it) remains can only set herself ablaze when she catches her reflection. Of all the changes that Branagh makes to the book, this is the one that seems closest to understanding the protagonist. He acts solely for himself, without considering how Elizabeth will feel if he succeeds in reviving her. It’s almost childish.

Though I keep harping on about Branagh’s fundamental misunderstanding of the protagonist’s major failures as a human being, there are ideas at play in the film. Ideas about God, parenthood, romantic and familial love, and the cost of the relentless drive to succeed. The film is almost breathless in its desire to communicate these ideas, to the extent that it feels both overstuffed and undercooked. This is really much more Kenneth Branagh’s Frankenstein than it is Mary Shelley’s, often to its detriment. And yet, for all its flaws, I cannot hate an interesting failure. The more I think about it, the more I appreciate the big swings it takes, even if many of them don’t work or actively irritate me. In that sense, I suppose it’s a worthy successor to Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Maybe next year I’ll review Stephen Sommers’ The Mummy as a palate cleanser. Who knows?

Until then, Happy Halloween! Later days.

- Branagh, Kenneth. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein — The Classic Tale Reborn. Pan Books, 1994.

- Wikipedia contributors. “Presumption; or, the Fate of Frankenstein.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 21 Aug. 2023. Web. 31 Oct. 2023.

- Shelley, Mary. Frankenstein, The Original 1818 Edition. Corrington Publishing LLC, 2020.

Pingback: Octoberween: ‘Frankenstein’ | Rooster Illusion