Sherlock Holmes is one of the most popular characters in all of fiction. IMDb credits him with 301 screen appearances, which puts him ahead of other prominent British figures like King Arthur, Frankenstein’s Monster, and Robin Hood, but still over 200 appearances behind Dracula. When a character reaches such a high level of familiarity in the public consciousness, it’s difficult to think of anything original to do with him, which is how we end up with gritty re-imaginings like the upcoming Robin Hood: Origins, an actual title of an actual movie. Other times, you think, “Gosh, I love this character, let’s make him really sad,” and in doing so produce a refreshingly different twist on a well-known icon.

Sherlock Holmes is one of the most popular characters in all of fiction. IMDb credits him with 301 screen appearances, which puts him ahead of other prominent British figures like King Arthur, Frankenstein’s Monster, and Robin Hood, but still over 200 appearances behind Dracula. When a character reaches such a high level of familiarity in the public consciousness, it’s difficult to think of anything original to do with him, which is how we end up with gritty re-imaginings like the upcoming Robin Hood: Origins, an actual title of an actual movie. Other times, you think, “Gosh, I love this character, let’s make him really sad,” and in doing so produce a refreshingly different twist on a well-known icon.

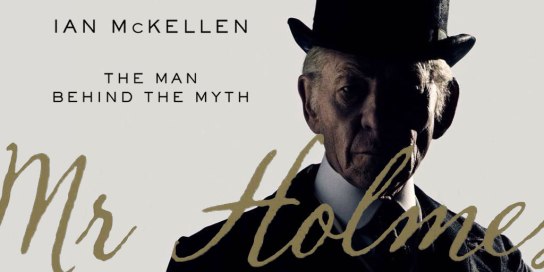

Mr. Holmes (2015)

The Plot: An elderly, senile Sherlock Holmes (Ian McKellen) lives a lonesome life of self-exile in a remote cottage, looked after by the recently widowed Mrs. Munro (Laura Linney) and her young son Roger (Milo Parker). As his memories fail him, Holmes tries to recall the details of the case that prompted his reclusion in the first place, a mystery revolving around a woman (Hattie Morahan) who seems to be spiraling into a deadly madness following two miscarriages. Like all his cases, the late Dr. Watson wrote a popular novel about this mystery, but something about the literary rendition disagrees with Holmes’ sneaking suspicion that he made a terrible and tragic mistake decades ago. As his mind deteriorates, Holmes must retrospectively solve the case in order to achieve solace before his impending death.

Sherlock Holmes is old and has a bad memory? Well, there’s your originality, right? Sadly, it’s not that simple. Age is a pretty superficial thing to change about a character. Sherlock Holmes is the world’s greatest detective, a mind of unflappable logic and deduction, and he knows it, which makes him incredibly arrogant and not really all that relatable. This is a guy who identifies modesty as a form of deception. I have always preferred the Watson character; where Holmes is cool and distant, Watson possesses enough human characteristics to make him… well, not a robot. Here we have a Holmes story without Watson, so immediately the most prevalent human component has disappeared. Fortunately, in tacking senility onto age, writer/director Bill Condon (based on the novel by Mitch Cullin) has managed to dilute Holmes’ self-confidence.

Unsurprisingly, Ian McKellen does a wonderful job with this. His rendition of the character is brimming with doubt and frustration, but trying desperately to remain the impersonal calculator that brought him such success in the past. He seems simultaneously reluctant and compelled to develop meaningful relationships with his landlady and her son, genuinely interested in them, and yet resistant to abandon Cumberbatch’s high-functioning sociopathy. McKellen’s performance excels in suggesting why this is. Obviously, he misses the feeling of being the best, of being indomitable, but there’s another facet to it. Since he plays a real Sherlock Holmes who exists in a world alongside a fictional Holmes, penned not by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, but instead by the narrator of the stories, Dr. Watson, McKellen’s Holmes has gotten caught up in the way others perceive him as well and, more importantly, how Watson wrote him. Holmes misses Watson; he misses that human element, and he wants to honor Watson’s memory, but doesn’t quite know how to do it.

Okay, so far I think we’re doing good things to Mr. Holmes. Doubt and sadness are good, but at its core, isn’t this story just another mystery? Doesn’t Holmes have to solve it the same way he solved every other mystery? SPOILERS. No. Towards the end of the film, of course, Holmes does remember what happened to the would-be mother Ann Kelmot; he remembers why he chose exile, why he failed. AGAIN, SPOILERS. He did solve the mystery behind Ann’s state and her intentions, he uncovered the facts. What he fails to understand, though, is the truth. There’s no logical solution to the abject pain of loss. Holmes gives her the facts after discovering her intentions to kill herself (not her husband, as initially suspected), and talks her down with a rational argument for why she should keep on living, but that’s not good enough. Damn, this scene is so well done in the movie I’m actually getting choked up thinking about it.

AI-Film

That moment when you realize that you’ve just made a huge mistake. That’s hard to capture in one look.

Mr. Holmes ends up as a valuable lesson to all those who seek to continue the legacies of popular characters: you can do more with them. The problem with Sherlock Holmes, and Batman and Superman and most figures who have acquired that kind of “legendary” status, is that the accepted idea of the character eventually takes place of any sort of relatable humanity. It’s fun to watch Batman beat up criminals, but I would rather delve into the psyche of Bruce Wayne and try to understand the mentality of a man who dresses up like a bat to fight crime. It’s fun to watch Holmes outwit even the cleverest criminals, but entertainment can be hollow without the support of real character. Mr. Holmes succeeds in going that extra mile where so many other incarnations of Holmes fail.

Reblogged this on bossogwo.